Traditionally, the only viral infections of concern during pregnancy were those caused by rubella virus, cytomegalovirus (CMV), and herpes simplex virus (HSV). Other viruses now known to cause congenital infections include parvovirus B19 (B19V), varicella-zoster virus (VZV), coxsackieviruses, measles virus, enteroviruses, adenovirus, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Also of importance, because of the high mortality rate associated with infection in pregnant women, is the hepatitis E virus. Recently, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) has been implicated as a teratogenic rodent-borne arenavirus.

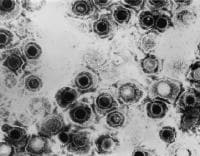

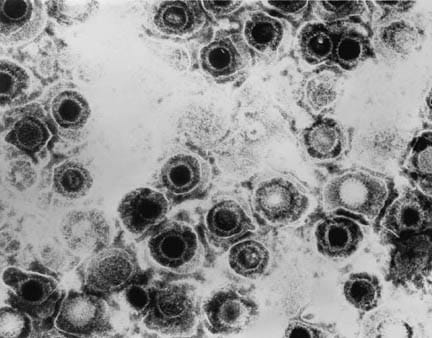

Viral infections and pregnancy. Transmission electron micrograph of herpes simplex virus. Some nucleocapsids are empty, as shown by penetration of electron-dense stain.

Worldwide, congenital HIV infection is now a major cause of infant and childhood morbidity and mortality, with an estimated 4 million deaths occurring since the start of the pandemic. The breadth and depth of this problem is beyond the scope of this article, which focuses on other viruses of concern.

Discussion

Congenital rubella syndrome in the first 16 weeks of pregnancy causes intrauterine growth restriction (sometimes termed intrauterine growth retardation), intracranial calcifications, microcephaly, cataracts, sensorineural defects, cardiac defects, hepatosplenomegaly, osteitis, or miscarriage. If rubella virus infection occurs in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy, up to 90% of patients have some manifestations of the congenital rubella syndrome. For infection at 12-16 weeks, the risk is approximately 20%.

Viral infections and pregnancy. Infant with congenital rubella and blueberry muffin skin lesions. Lesions are sites of extramedullary hematopoiesis and can be associated with several different congenital viral infections and hematologic diseases.

Congenital CMV infection is the most common congenital viral infection and results in intrauterine growth restriction, sensorineural hearing loss, intracranial calcifications, microcephaly, hydrocephalus, hepatosplenomegaly, delayed psychomotor development, and optic atrophy. Most infections (90%) cause no symptoms, but 10% cause microcephaly, thrombocytopenia, hepatosplenomegaly, intrauterine growth restriction, or a combination thereof. Of those who survive infancy, half eventually develop microcephaly, mental retardation, and sensorineural hearing loss. Seven percent of asymptomatic neonates develop sensorineural hearing loss or developmental delays during the first 2 years of life. Five percent eventually develop microcephaly and neuromuscular defects, and 2% develop chorioretinitis.

Thirty to 60% of women receiving obstetric care have serologic evidence of past HSV infection. Although both HSV-1 and HSV-2 may cause neonatal herpes, HSV-2 is responsible for 70% of cases. Ninety percent of infections are perinatally transmitted as a result of acquisition of the virus in the birth canal. HSV acquired in this manner has a 70% risk of dissemination and is associated with skin lesions, encephalitis, and neurological disability. Approximately 10% of infections are congenital, usually a consequence of the mother acquiring HSV during pregnancy and the fetus acquiring the infection transplacentally or via an ascending infection from the cervix. This route of infection is associated with intrauterine growth restriction, preterm labor, and miscarriage. The risk of neonatal herpes and death is highest in infants born to mothers who have not seroconverted at the time of birth.

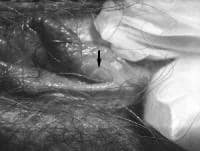

Viral infections and pregnancy. Blisters on the vulva due to a recurring herpes II (HSV-2) virus infection

B19V, the causative agent of erythema infectiosum (fifth disease), has been shown to cause fetal anemia, hydrops fetalis, myocarditis, and intrauterine fetal death. Infection occurs most commonly in the winter and spring. Thirty to 40% of pregnant women are seronegative for B19V and are thus susceptible to infection. Various studies have estimated that 3-14% of intrauterine fetal deaths occur in the setting of B19V infection. Second-trimester infections have been studied most frequently because infection in this trimester carries a 1-3% risk of hydrops; however, infection in any trimester may result in intrauterine fetal death. B19V infection accounts for 15-20% of nonimmune hydrops fetalis. Most of the deaths in the third trimester have not been associated with hydrops.

VZV is a common virus that carries risk for both mother and fetus during pregnancy. Morbidity and mortality rates are much higher in adults than in children. If the mother develops primary varicella during pregnancy, especially in the third trimester, she is at risk for varicella pneumonia. Pneumonitis is 25 times more common in the adult population. Subclinical infection also may play a role in neonatal morbidity. The mortality rate was 36%; the rate is now closer to 10%. Congenital varicella syndrome (CVS) results in spontaneous abortion, chorioretinitis, cataracts, limb atrophy, cerebral cortical atrophy, and neurological disability. Spontaneous abortion has been reported in 3-8% of first-trimester infections, and CVS has been reported in 12%.Acquisition of infection by the mother in the perinatal period poses a risk of severe neonatal varicella, with a mortality rate of 30%.

Notably, varicella vaccine (live attenuated virus) is not administered during pregnancy; however, inadvertent vaccination of pregnant women is not an indication for termination of pregnancy. The Varicella Vaccination in Pregnancy Registry, a prospective outcomes monitoring system, has not indicated any adverse risk related to the varicella vaccine in pregnancy.

Some studies have linked coxsackieviruses to miscarriage, neurodevelopmental delay, and cortical necrosis; however, one study showed no effect of maternal infection in the third trimester. One study associated the presence of coxsackievirus with respiratory failure and global cognitive defects.

Measles virus infection (rubeola) during pregnancy, as with VZV infection, tends to be severe, with pneumonitis predominating. Rubeola is associated with spontaneous abortion and premature labor. Neonates born to mothers with active measles virus infection are at risk of developing measles, but no congenital syndrome has been described.

LCMV has been associated with sporadic cases of congenital infection worldwide. Affected infants demonstrate chorioretinitis, hydrocephalus, mental retardation, visual impairment, and possible intrauterine death. Unlike congenital CMV and rubella, hearing deficits and hepatosplenomegaly are rarely seen in congenital LCMV.

Other viruses postulated to cause congenital infections include enteroviruses, echovirus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and adenovirus.A recent article in the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report discussed a single case of West Nile virus infection in the mother and associated fetal anomalies in the newborn. A causal link has not been determined.

Pathophysiology

Congenital viral infection is usually transmitted transplacentally, with the efficiency of transmission depending on the particular virus.

CMV transmission can occur transplacentally, intrapartum, and during breastfeeding. Of the 3, transplacental transmission is associated with congenital infection and CNS sequelae.

Primary HSV infection is transmitted transplacentally, whereas secondary HSV leads to intrapartum transmission. Both HSV and VZV have tropism for neural tissue. Infection of developing nerve bundles may explain limb atrophy and chorioretinitis in CVS.

B19V has a tropism for the fetal bone marrow and liver, causing apoptosis of erythroid precursors and thus inhibiting erythropoiesis. Fetal liver erythroblasts exhibit viral DNA and pathognomonic changes of B19V infection. Myocardium has also been affected, causing myocarditis and resultant heart failure.

Frequency

Congenital rubella syndrome has decreased in frequency since the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine was introduced in 1988 and now mostly occurs in immigrants to the United States.

The estimated incidence of primary B19V infection in pregnancy ranges from 1-5%.

CMV is the most common virus known to be transmitted in utero, occurring in approximately 0.5-1.5% of births.Approximately 30% of maternal infections during pregnancy result in congenital infection.

In some parts of the United States, neonatal herpes occurs in up to 1 per 3200 live births. The rate of HSV-2 seroconversion during pregnancy is estimated to be 0.2-4%.

Varicella occurs in approximately 1-7 of 10,000 pregnancies.

LCMV infection occurs in the Americas and Europe, in areas where people are exposed to the host species of hamsters, Mus domesticus and Mus musculus. Infections tend to occur in focal geographic areas in autumn.

Morbidity/Mortality

Symptomatic neonates with congenital CMV infection have a 10-15% mortality rate, although recent data suggest that mortality rates are probably less than 5%.

Neonates with HSV infection acquired perinatally have a 65% mortality rate if untreated and a 25% mortality rate if treated.

Patients with CVS have a 30% mortality rate.

LCMV infection is rarely fatal in the adult host, but fetal acquisition may lead to intrauterine death.

Up to 20% of pregnant women who acquire hepatitis E develop fulminant hepatic failure.

Clinical

A history of typical rubella rash starting in the face or neck, along with suboccipital lymphadenopathy, arthralgias, fever, and cough, suggests rubella. Immunization history and rubella titers (usually obtained at the outset of pregnancy) are important. Immigrants from developing countries are often inadequately immunized; thus, the alert clinician inquires about rash acquired during early pregnancy in this population.

Measles virus infection is also associated with inadequate immunization and is characterized by cough, coryza, conjunctivitis, and Koplik spots, ie, bluish-gray spots on a red base in the buccal mucosa.

CMV infection of the mother is most likely due to reactivation of latent virus and thus causes no symptoms or manifests as low-grade fever, malaise, and myalgias. Acute infection is usually asymptomatic but may present with a mononucleosislike picture, with fever, fatigue, and lymphadenopathy.

LCMV infection of the mother may also present as nonspecific flulike symptoms, including fever, malaise, myalgias, and headache; it may progress to aseptic meningitis in the adult patient but is usually self-limited in the nonpregnant adult, with resolution in 2-3 weeks.

Asking about previous HSV lesions is important; however, approximately 70% of women who have been exposed to HSV do not know they are infected.

A faint macular rash associated with arthralgias may be a clue to B19V infection in the mother.

Previous VZV infection or immunization protects the mother from VZV during pregnancy. If the mother develops varicella within 5 days before delivery to 2 days after, her neonate is at high risk for neonatal varicella. Therefore, a known lack of exposure should prompt further testing of the antibody response.

A clinical history of exposure to another person infected with rubella virus, measles virus, VZV, CMV, or HSV is important. Occupational exposure to children and/or having children at home are risk factors for CMV, VZV, and B19V infections.

Physical

Fever in a pregnant patient should alert the clinician to the possibility of viral infection.

Skin symptoms related to HSV and VZV infection include a vesicular rash. For rubella virus infection, the rash is maculopapular in nature, starting on the face and trunk. Measles virus infection rash is maculopapular and begins on the face, then involves the extremities, including the palms. Koplik spots appear before the rash and are composed of bluish-gray spots on a red base in the buccal mucosa. B19V infection is indicated by a pinkish macular rash on the face or trunk or a gloves-and-socks distribution. Coxsackievirus infection is associated with a nondescript maculopapular rash or, in the case of hand-foot-and-mouth disease, a vesicular rash on the palms, soles, and oral mucosa.

Lymph node symptoms of rubella virus infection include suboccipital lymphadenopathy.

LCMV may present with a maculopapular rash, lymphadenopathy, and papilledema if meningitis is present.

Lung symptoms of tachypnea and diffuse rales or wheezes in a patient with varicella suggest pneumonitis.

Differentials

In addition to the previously mentioned viral infections, fetal abnormalities can be caused by Toxoplasma gondii, toxins, vitamin deficiencies, alcohol ingestion, and placental abnormalities.

Workup

Lab Studies

Rubella virus infection in the mother is confirmed with immunoglobulin G and immunoglobulin M serology.Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or viral culture of amniotic fluid has been used in difficult cases. Infants can be diagnosed with serology or viral cultures of the throat or urine.

CMV infection is determined with antigen, PCR, or culture of amniotic fluid. Quantitative PCR may also be used. Neonates can be diagnosed with viral culture of urine or PCR of urine or blood.Rapid culture techniques provide results in 24-36 hours.

Type-specific antibodies to HSV-1 and HSV-2 are used to confirm past exposure and current infection of the mother. HSV culture or PCR can be used to diagnose lesions found during pregnancy. If a neonate is exposed to HSV lesions, viral cultures of the throat, eyes, nasopharynx, and rectum are generally performed at 5-10 day intervals to screen for development of infection. HSV PCR of amniotic fluid is sensitive but may not correlate with neonatal HSV infection.

Traditionally, B19V infection has been confirmed with immunoglobulin M serology; however, PCR has recently been shown to be more sensitive and can be used with amniotic fluid, cord blood, maternal serum, or placental tissue.

Serology can be used to confirm VZV infection and previous exposure in the mother. Viral culture can be performed on skin lesions. Diagnosis in the infant is difficult because only 27% have an immunoglobulin M response. Serology for VZV immunoglobulin G can be performed after the sixth month. Viral culture in infants has not been found to be helpful. PCR of skin tissue may be useful.

Coxsackievirus infection can be confirmed by serology in the mother. In situ hybridization or reverse transcriptase PCR of tissue can be performed on the newborn.

Measles virus infection can be confirmed by immunoglobulin M serology.

LCMV infection can be diagnosed based on an immunoglobulin M enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) of cerebrospinal fluid or serum. CSF pressure is generally increased, with protein levels of 50-300 mg/dL and lymphocytes. Patients may also exhibit leukopenia or thrombocytopenia.

Imaging

Fetal ultrasound has been used to assess for hydrops appearance (ie, a halo surrounding the fetal cranium and other structures, representing skin edema), fetal intracranial calcifications, hydrocephalus, microcephaly, cardiac defects, and hepatosplenomegaly.

Chest radiography should be performed in any pregnant patient with a recent VZV infection and respiratory symptoms.

Echocardiograms should be performed postnatally in infants with congenital rubella syndrome to look for cardiac defects, including patent ductus arteriosus.

Diagnostic Procedures

Amniocentesis or chorionic villous sampling can assist in confirming infections with rubella virus, CMV, B19V, and, possibly, HSV.

Treatment

Medical Care

Treatment is supportive in nature, to help minimize maternal complications such as pneumonitis in measles and varicella. Zoster immunoglobulin (ZIG) administration at the time of a known exposure can prevent or reduce the severity of chicken pox. Upon clinical evidence of disease, ZIG is ineffective. Similarly, support for the neonate is important, especially with neonatal HSV and VZV infection. Intrauterine transfusion can be performed in fetuses with a hydropic appearance and documented anemia. In addition, in some cases of B19V infection, administration of high-titer intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) has been successful.

Echocardiograms should be performed postnatally in infants with congenital rubella syndrome to look for cardiac defects, including patent ductus arteriosus.

Surgical Care

If primary or recurrent HSV genital infection occurs late in pregnancy, elective caesarian delivery is performed to prevent neonatal infection, although neonatal infection is still possible via transplacental passage of HSV prior to birth.

Consultations

Obstetricians may be consulted if any treatment is necessary and for complicated procedures.

Medication

Clinical trials of ganciclovir for postnatal treatment of congenital CMV infection are ongoing. Some evidence already indicated that treating symptomatic neonates with CMV infection prevents hearing deterioration at age 6 months and may prevent hearing deterioration at age 1 year or older.

Acyclovir has been shown to prevent recurrences of HSV lesions during pregnancy and is indicated for treatment of neonatal HSV.In the Acyclovir in Pregnancy Registry, in which more than 1200 women had documented exposures to acyclovir, no adverse effects were directly attributed to this drug.

Acyclovir is also indicated for the treatment of varicella pneumonia during pregnancy and may be helpful for neonates born with CVS in order to stop the progression of eye disease. No studies have been performed to determine if treatment of varicella during pregnancy prevents CVS.

Follow-up

Further Inpatient Care

Some pregnant patients with varicella may require admission for treatment if pneumonitis is suggested.

Further Outpatient Care

Infants with confirmed congenital CMV infection, even if asymptomatic at birth, should have frequent audiometric evaluations through at least age 6 years

Deterrence/Prevention

Animal studies with CMV immunization look promising for prevention of congenital CMV infection and complications.CMV vaccines currently in various stages of preclinical and clinical testing include protein subunit vaccines, DNA vaccines, vectored vaccines using viral vectors, peptide vaccines, and live attenuated vaccines.

VZV immunization of unexposed adolescent girls helps prevent CVS. If an unimmunized woman who has never had varicella is exposed to VZV during pregnancy, VZV immune globulin should be given within 72 hours of exposure to prevent varicella.

Pregnant women who are seronegative for HSV can prevent infection acquisition by sexual abstinence. An alternative would be the use of condoms and abstinence from oral-genital sex. The results of several trials suggest that the use of acyclovir decreases the expression of genital herpes at term and, thus, the need for a cesarean deliver. However, larger trials are needed to confirm these data.

Avoidance of rodents, including mice and hamsters, may help prevent LCMV infection.

Prognosis

Prognosis depends on the viral syndrome and the severity of the initial infection.

Patient Education

Educating the pregnant patient to avoid contact with persons with viral infections and frequent hand washing when handling children can prevent infection. If exposure does occur, the patient should seek immediate assistance for postexposure prophylaxis with varicella immunoglobulin.

Miscellaneous

Medicolegal Pitfalls

A missed diagnosis of fetal or maternal infection that could be prevented or treated could result in liability.

Multimedia

| Media file 1: Viral infections and pregnancy. Transmission electron micrograph of herpes simplex virus. Some nucleocapsids are empty, as shown by penetration of electron-dense stain |

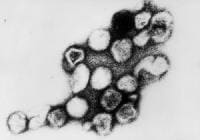

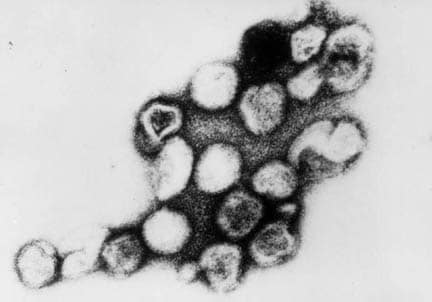

| Media file 2: Viral infections and pregnancy. Transmission electron micrograph of rubella virus. |

| Media file 3: Viral infections and pregnancy. Blisters on the vulva due to a recurring herpes II (HSV-2) virus infection. |

2 comments:

Thank you for your article. I try to raise CMV awareness too.

Lisa Saunders

Author of "Anything But a Dog! The perfect pet for a girl with congenital CMV." anythingbutadog.blogspot.com

good,you cover a valuable information in your blog..keep going

Post a Comment